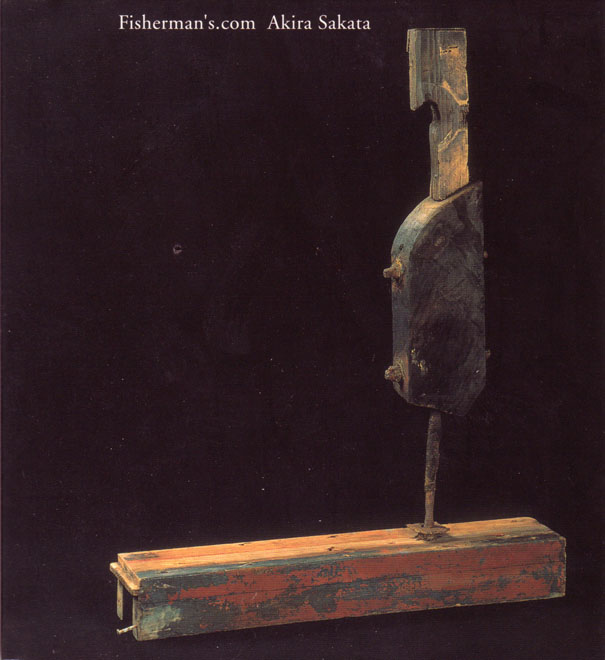

AKIRA SAKATA

1/ Kaigara-bushi 14.43

2/ Ondo no hunauta 9.49

3/ Saitaro-bushi 8.43

4/ Wakare no ipponsugi 14.28

Recorded and mixed at Orange Music Sound Studio, New Jersey, October 17-19, 2000

Engineered by Robert Musso

Produced by Bill Laswell and Akira Sakata

Mastered October 21, 2000 by Michael Fossenkemper at Turtletone Studio

Bancamp remaster by James Dellatacoma at Orange Music, West Orange, NJ

Akira Sakata: vocal, alto saxophone, synthesizer; Pete Cosey: electric guitar; Hamid Drake: drums, congas; Bill Laswell: electric bass, synth bass.

2001 - Starlets'/Dogtail (Japan), EOCD-0002 (CD)

2021 - Bill Laswell Bandcamp (Bassmatter Subscription Exclusive)

Laswell has been at the center of more than a few musical revolutions: He worked with Herbie Hancock to produce the 1980s classic "Future Shock" and, more recently, in collaboration with several Funkadelic alumni to yield "Funkronomicon" in 1995. Indeed, Laswell has worked with an amazing range of performers, from Ginger Baker and Brian Eno to Afrika Bambaataa and Motorhead, to cite only a few.

Sakata himself is something of a legend in Japan's free-jazz world, having headed a number of bands since his debut in 1969 with the group Saibo-bunretsu. A vocalist and alto-sax player, as well as a writer and actor, Sakata has over 20 albums to his credit, including two -- "Noise of Trouble" (1986) and "Mooko" (1988) -- recorded with Laswell.

Sakata and Laswell's latest joint effort is rich with the producer's trademark sound: heavy bass layered with tribalistic drumwork (courtesy of accomplished drummer Hamid Drake) and a dreamy, other-worldly ambience. The album is ostensibly a reworking of traditional Japanese folk songs, although by the time Sakata is through, it's hard to find any resemblance to the original material. On saxophone, Sakata emphasizes energy more than refinement, perhaps at the expense of melody. Nevertheless, there is a deeply satisfying primal energy to his vocal work. The result comes across like a prehistoric man celebrating the discovery of fire.

Overall, the album straddles a range of contrasts, between the ancient and the modern, the tuneless and the rhythmic. Its self-indulgence at times may lose some, but those accustomed to the spontaneous style that comes with the territory will surely be rewarded.

"Fisherman's.com" should be approached with an open mind. If standard fare is your bag, then look elsewhere. But for the eclectically minded, this is one dot-com that won't go bust.

Junji Nishihata (courtesy of the Japan Times website)

Originally released in 2001, Fisherman’s.com is Japanese free-jazz stalwart Akira Sakata’s ode to folksongs of the sea, reimagined and repurposed as seeds for avant distortions. Featuring Sakata on alto saxophone and vocals, Bill Laswell on bass, Pete Cosey on guitar, and Hamid Drake on drums, it’s an intensely personal statement on the fluidity of tradition.

“Kaigarabushi” opens with a fisherman’s song from the region of Tottori in western Japan. Sakata’s singing of it has a mineral quality that will taste familiar to admirers of Mikami Kan. Like a blind minstrel who feeds only the ears of ghosts longing to relive their exploits, he touches listeners from temporal distances. The band at his side sets up a row of large beakers, each filled to brimming with funk. Yet while Laswell and Drake are precisely measured, Cosey stirs up an amorphous mixture of colors through the flange of his talking guitar. His sound bleeds out the smallest facets of Sakata’s singing, and finds in their reimbursement an alluring style of damage. So, too, does the bandleader’s reed work pour on strange beauty.

“Ondo no funauta” sets out on more troubled waters before bass and drums drop an anchor of groove, while Cosey’s fins move in more mysterious ways below depths. By no coincidence, the song tells of boatmen handling a particularly treacherous strait in Hiroshima Prefecture, though one might never know those challenges for the skill with which the band navigates them. Neither does Sakata’s saxophone betray one wave of that treachery, as it emotes without fear, and blasts the surety of their experience beyond the ultimate fallibility of their technology.

“Saitarabushi” (incorrectly Romanized as “Saitarobushi”), another fishing song, also made an appearance on Sakata’s 1997 trio album, Do desho?! (How’s That?!). Here is the fruit of dangerous labors, the celebration a big catch with due ceremony. Sakata is soulful as ever over the band’s shoreline backdrop, even as Cosey portals in some modal ghost signatures of those who drowned long so. Laswell is thick and thin by turns, imprinting the sand but flying off with a harmonic in the same breath.

“Wakare no ippon sugi,” a ballad from the 1950s that clinched singer Hachiro Kasuga’s status as a pioneer of the Japanese enka form, is barely recognizable through Sakata’s filter—no small feat for such a famous tune. The forlorn lyrics tell of love lost under a cedar tree, a parting so sad that even the birds cry in the mountains. Not that a non-Japanese speaker would know this, given the upbeat presentation. All of which makes Sakata’s cries through the reed, and the guttural exhale with which he ends the album, that much more cathartic and emotionally relevant.

Tyran Grillo (courtesy of the ECM Reviews website)